Analysis: The story of our ancestors' diet is a fascinating tale of how environment and surroundings informed the food that was eaten

By James Mallory, Queen's University Belfast

If we can trust the scratch marks on the bones of animals retrieved from Irish caves, the earliest item on the Irish menu was reindeer venison from Castlepook Cave, Co. Cork, dated circa 33,000 BCE, followed by a meal of brown bear from Alice and Gwendoline Cave, Co Clare (c 10,500 BCE). These would generally be attributed to casual tourists who visited Ireland during the Ice Age and we do not really get much of an idea of the Irish menu until the earliest successful settlement of Ireland during the Mesolithic era, 8,000-4,000 BCE.

The Mesolithic saw the occupation of Ireland by colonists who came by boat across the recently formed Irish Sea. It was this water barrier that determined that Ireland was going to be far poorer in available foodstuffs than its neighbours as many of the plants, animals and fish that were found in Britain (then still connected to the Continent) and the rest of Europe never managed to find their way to Ireland.

While the earliest colonists had dined on the meat of aurochs (wild cattle), elk, red deer and wild boar at home, the only major source of meat in Ireland was wild boar. Moreover, the absence of wild boar from earlier faunas in Ireland has suggested that they too had been initially imported by the earliest human colonists who recognised that they were far more prolific even if they lacked the size of the other animals. How they were butchered or served we do not know as our major source is evidence of piglet trotters from the site of Mount Sandel, Co Derry.

From the Ulster Archaeological Society, Dr Ruth Carden discusses the Irish Cave Bones Project and various findings to date

The lack of meat highlights the importance of fish in the Mesolithic Irish diet. The primary species recovered are salmonids (salmon and trout) and eels who were captured during their seasonal runs, either employing spears or fish-weirs as have been recovered in Dublin. Coastal sites also indicate fishing for wrasse, whiting, and various species of cod. Shellfish were also collected and there is good evidence for the chance hunting of birds ranging in size from wood pigeon to capercaillie.

To all of these must be added the contribution of plants to the Irish diet, whose importance because of the difficulties of preservation is problematic. On a theoretical level, we know that Ireland possesses over 100 native edible plants. By far the best represented are hazel nuts (stored in pits to presumably give provide an additional food source during the winter) and which survive as charred remains. There is also some evidence for the exploitation of waterlily seeds.

About 4,000 BCE, Ireland saw an influx of new colonists who introduced farming and revolutionised the Irish diet. The meat menu was greatly expanded by the introduction of cattle, sheep, domestic pig, possibly goat and occasional red deer. However, the latter is so rare that it may have been introduced more for the utility of its antlers than its meat. Curiously, the introduction of a range of meat products appears to have pushed fish off the diet other than some evidence for gathering shellfish.

From St Patrick's Festival, what prehistoric Ireland's diet looked like

In addition to meat, dairy products are also in evidence in the form of fatty residues on Neolithic pots. There is a presumption that the milk was primarily derived from cattle (sheep and goats are still a possibility), which is somewhat problematic because genetic analysis of Neolithic populations shows they lacked lactase persistence and the ability to deal with the more dire problems of consuming raw milk as an adult. Ireland today has one of the lowest percentages of lactose intolerance populations worldwide (4%), but it would have been problematic for the population in the Neolithic era to consume milk. For this reason it is likely that the milk was subsequently processed into cheese which greatly reduces its harmful effects.

The charring of seeds has left clear evidence that the diet also involved the consumption of wheat and barley, but hazel nuts still continued as an adjunct to the diet and there are also traces of wild fruit such as carb-apples.

The introduction of ceramics provides clear evidence of wet cooking and the boiling of plants and meat in a pot. How precisely cereals were exploited still remains a problem as there has been no evidence of bread (it would be a remarkable find anyway) and analysis of the food residues from Neolithic pots have tended to recover traces of milk fats rather than cereals, although these may simply have been drowned out by the more abundant fats. In addition to the use of pottery, there is clear evidence of hot-stone cooking at this time where stones would be heated and dropped into a trough full of water to raise the temperature to boiling.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

The Bronze Age (c 2,500 – 600 BCE) does not see as much of a shift in diet as population, as colonists bearing a new culture (the Beaker culture) arrived in Ireland and began altering the genome of its population towards that of the current population. The meat diet remained largely the same as before and we now have evidence for the occasional consumption of goat and horse as well as dog.

There is some evidence for fishing at Dún Aonghasa on Aran Mór, but there is no evidence otherwise of a fishing revival. The cereal diet remained wheat and barley with the latter predominating. A good example comes from a Late Bronze Age hillfort (c 1,000 BCE) where 99% of the 12,000 charred seed remains consisted of naked barley. It has been suggested that naked barley, which lends itself to being more easily ground into flour, might indicate that it was being utilized for baking bread rather than boiled as a gruel.

The Bronze Age is also the main period of hot-stone cooking which, employing a term found in Geoffrey Keating's Foras Feasa ar Éirinn, are usually described in archaeological literature as fulachtaí fia. Over a thousand such sites have been excavated where they display their troughs, unlined or lined by stone or wood, and mounds of burnt stone. Bones from all the major species of mammals have been recovered from the sites, with the predominant animal being cattle and fishbones being conspicuously absent.

We need your consent to load this rte-player contentWe use rte-player to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

The purpose of these sites has been extended to include brewing beer, dyeing or tanning, and bathing, but cooking remains the primary use. Boiling meals in ceramic vessels continued, but we also see the emergence of metal vessels, especially bronze buckets and large bronze cauldrons. All of these cooking strategies are suggestive of food preparation probably exceeding that of a nuclear family and point to communal feasting.

The evidence for food in the Iron Age (600 BCE – 400 CE) is probably skewed by the major excavations that have been undertaken at what have been regarded as provincial royal sites such at Tara, Co Meath, Dún Ailinne (Knockaulin), Co Kildare, Emain Macha (Navan Fort), Co Armagh and Cruachain (Rathcroghan), Co. Roscommon. On these sites, we would expect major feasting. If so, beef was the most numerous item on the menu at Tara and Dún Ailinne while pork was found in greater numbers at Emain Macha (though beef provided a greater quantity of meat overall).

There were two interesting changes to food preparation. Since the Neolithic, grain had been ground on flat saddle querns, but we now find Ireland introduced to the rotary quern. This was labelled as a beehive quern because of its appearance, which involved a top stone with a funnel-like hole at the top and a small hole to hold a wooden handle on the side which could rotate over a flat stone below.

A second major change was the apparent disappearance of ceramic pottery on these sites as Ireland seemingly abandoned clay-built vessels leaving archaeologists to speculate on how Iron Age cooking was carried out. We know that they had recourse to wooden vessels and there is some evidence for metal vessels but the abandonment of a technology that had served for nearly four thousand years has remained a mystery.

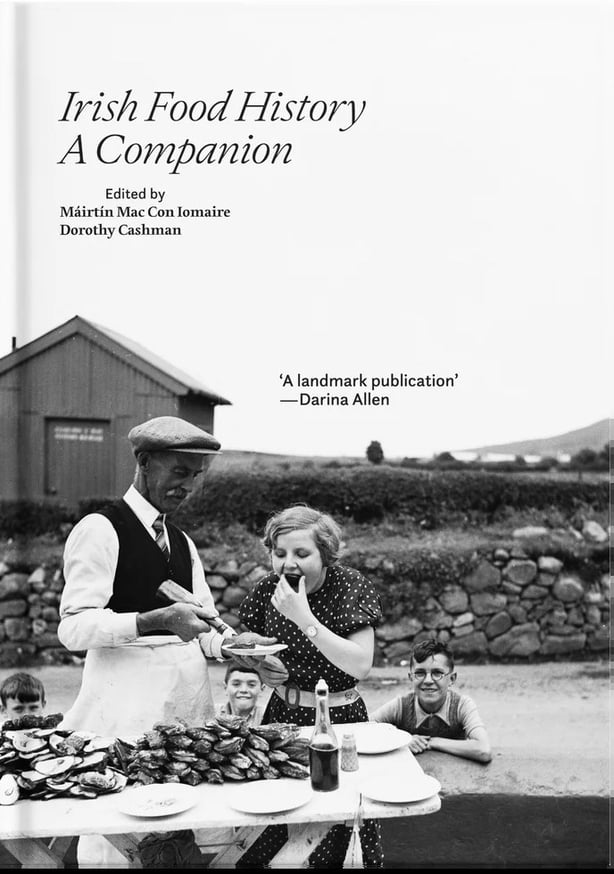

This is an edited extract of the author's piece as published in Iri sh Food History: A Companion (Royal Irish Academy)

Follow RTÉ Brainstorm on WhatsApp and Instagram for more stories and updates

Prof James Mallory is Emeritus Professor at the School of Natural and Built Environment at Queen's University Belfast